On Monday, 01/06/2020, look for the Mayor to be talking dollars and cents ($200M+?) as he has in the first year after every election since 2000. How long will the meeting go? Less than 4 hours would be an improvement over 2016.

He knows only a few are paying attention and he is emboldened by his re-election and the need for the final “Signature Project”

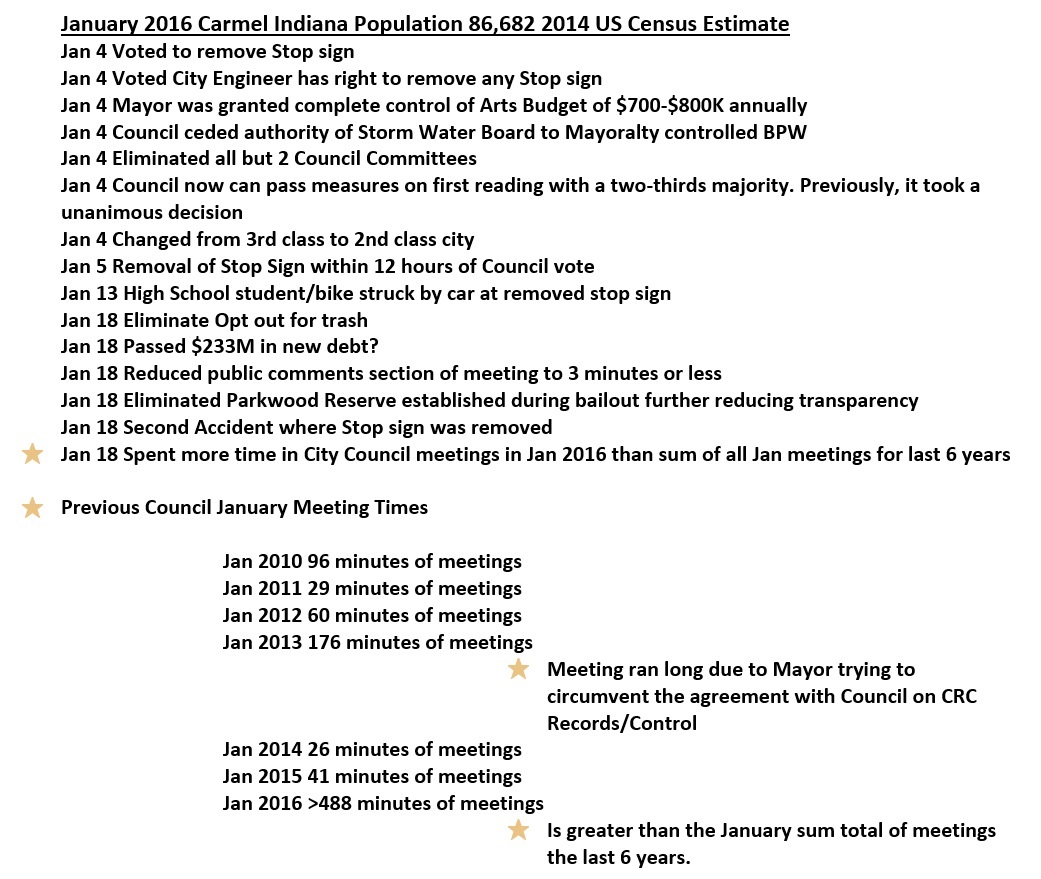

The graphic below illustrates the historic month in Carmel History that was 2016!

This IBJ story from April 2012 and was a precursor to the August ’12 bailout discussion.

————————————

“After Brainard and the city council reached an impasse on financing the arts complex in 2009, the redevelopment commission issued $57 million in debt that carries interest rates ranging from 5.75 percent to 9.25 percent.

The certificates of participation are backed by TIF money, but they take a subordinate position to earlier debt issues.

The certificates, underwritten by Oppenheimer & Co. Inc., were sold only to institutional buyers in a private placement, rather than through the open market. That means it’s impossible to see how the market would view the credit risk.

There’s no credit rating on the certificates. An official statement to investors discloses that none was sought, “nor is there any reason to believe the District would have been successful in obtaining an investment-grade rating for the certificates, had application been made.” ” (Excerpted from story below)

Carmel mayor seeks deal on maxed-out TIF

Kathleen McLaughlin, Indianapolis Business Journal

Monday, April 2, 2012, 9:46 AM

Carmel Mayor Jim Brainard might relinquish his political trump card in an effort to refinance some of the $240 million in debt that are weighing on the city’s tax-increment finance districts.

Brainard said he’s looking to compromise with city councilors who want to have the final say on future debt incurred by the Carmel Redevelopment Commission. The mayor-appointed commission has rung up $139 million since 2009, all independent of the council. Now it needs almost every dollar of $21 million in annual TIF revenue to cover payments.

“We think that they have a role to play as the fiscal body,” Brainard said of the council in a phone interview from Paris, where he was visiting his daughter.

Brainard said he’s working on a proposal that would trigger council oversight of the six-member commission in some cases, depending on the amount of debt or revenue-to-payment ratios. He plans to have debt-refinancing options on the table when he meets with the council’s finance committee this month.

The redevelopment commission took on most of its debt to complete the Center for the Performing Arts, which opened in January 2011. Carmel has little chance of refinancing the high-interest, high-risk debt issues without backing from residential property tax or other non-TIF-district sources, bond analysts said.

“Personally, I don’t think it would be that good unless the county or somebody is willing to put a backstop in there,” said Ji Young Jung, a municipal credit analyst who has covered Indiana for Breckenridge Capital Advisors in Boston.

A local bond trader who did not want to be identified said Carmel could shed the 8-percent interest it’s paying on a chunk of the debt for a more reasonable 4.5 percent if the new issues are backed by the city’s entire property-tax base.

Since the 2008 real estate bust, bond investors don’t buy claims that rising property values inside TIF districts will generate sufficient revenue, the bond trader said. “The investing public is much more careful about TIFs than they used to be.”

Pledging Carmel’s full faith and credit would take some punch out of Brainard’s common retort. When critics complain about the cost of downtown development projects, especially the $175 million performing arts center, Brainard points out that TIF revenue on commercial property—not the city’s residential base—pays the bills.

Carmel’s lucrative TIF districts serve as a handy political shield, and not only for Brainard.

Although Council President Rick Sharp was part of the contingent that balked at financing a parking garage for the performing arts complex, he didn’t object to the redevelopment commission’s helping provide a $5.5 million subsidy for its operations. The commission’s move last fall saved the council from taking a vote on the potentially controversial subsidy.

Heavy TIF use

Cities set up TIF districts to spur economic development. Additional property taxes on new developments within their boundaries go toward paying off debt issued to pay for roads, sidewalks and new buildings—instead of into the general fund.

Carmel has created 25 TIF areas. They include specific projects, such as Buckingham Cos.’ urban-style Gramercy, and whole commercial corridors.

No other Indiana city of Carmel’s size has TIF districts generating as much as $21 million, said Mike Shaver, principal of the Carmel-based consulting firm Wabash Scientific, which helped Carmel plan its TIF areas.

The Carmel Redevelopment Commission, which controls the TIF revenue, has drawn more attention over the past few years because of its independence and creative financing.

In Indiana, redevelopment commissions can’t issue bonds on their own, but Brainard and the commission have found ways to work around that by issuing “certificates of participation” and other forms of debt. A 2010 opinion from Attorney General Greg Zoeller supported that narrow interpretation of the law.

Since then, Sen. Luke Kenley, R-Noblesville, has pushed legislation that would require those agencies to seek approval from a local elected body. The appointed commissions are like “shadow governments” because they control large amounts of tax revenue but don’t answer to voters, Kenley said this year. His bill died in the House.

Sidestepping impasse

After Brainard and the city council reached an impasse on financing the arts complex in 2009, the redevelopment commission issued $57 million in debt that carries interest rates ranging from 5.75 percent to 9.25 percent.

The certificates of participation are backed by TIF money, but they take a subordinate position to earlier debt issues.

The certificates, underwritten by Oppenheimer & Co. Inc., were sold only to institutional buyers in a private placement, rather than through the open market. That means it’s impossible to see how the market would view the credit risk.

There’s no credit rating on the certificates. An official statement to investors discloses that none was sought, “nor is there any reason to believe the District would have been successful in obtaining an investment-grade rating for the certificates, had application been made.”

The certificates helped pay for theater spaces, offices and a parking garage at the performing arts complex. The council approved financing for the first component of the project, the Palladium concert hall, in 2005 with $80 million in lease-rental revenue bonds.

Standard & Poor’s rated those bonds AA+, which is just below the highest rating of AAA.

Asked whether the interest rates on the certificates gave him pause, Brainard said, “Sure, but we anticipated refinancing these in bulk at some point over the next year or two.”

Installment purchase contracts with banks account for another $80 million of the commission’s debt. Much of that was to finish building the performing arts center.

Not all of those contracts would be eligible to roll up into municipal bonds, said Sharp, the council president. He hopes the city can help restructure $60 million to $70 million of the commission’s debt.

Market conditions could delay completing the deals.

“We’ve seen advance refunding, which is what this would be, off dramatically from previous years,” said David Madigan, chief investment officer at Breckenridge Capital Advisors.

Bond issuers that want to refinance have to buy U.S. Treasuries to cover the outstanding debt. For issuers to come out even, Treasury yields would have to match what they’ll pay on the new bonds.

Right now, Treasury yields are lower than even some tax-exempt municipal bonds. That situation would put a city in the red on a refinancing.

Brainard’s critics have seized on the fact that the redevelopment commission’s TIF revenue is maxed out, with virtually all earmarked for debt payments.

Brainard wants some wiggle room, but he thinks Carmel is still in an enviable financial position.

“One large office building built in the TIF district would get coverage ratios back to where we’d like them to be,” Brainard said. “There’s no crisis.”

Shaver, the Wabash Scientific principal who helped Carmel set up its TIF districts, said he’s impressed by how much money they’ve generated, but less so by how quickly the commission spent it.

“To have the most successful redevelopment commission in Indiana end up like this causes me great concern.”

—————————————

The story ends in 2016 when the City Council adopted the Rubberstamp Platform, making nearly all decisions the sole domain of Mayor Jim Brainard.