Last month in our social feed, I shared an interesting piece from Greater Greater Washington on the glut of vacant office space in Washington DC. In a city with explosively high housing prices, the article questions why some of the reportedly 14 million square feet of vacant space could not—or was not—being converted for residential use. If half of it was converted to 1,200 square foot units, that would be around 5,000 new units. According to the same site, that is more units than were permitted to be built in DC in all of 2016.

Some people on Facebook were rather dismissive of my take and the article in general. Come on, Chuck. The market will take care of this problem. Indeed, I think it will, but not how you might hope. The way commercial real estate is financed has some strange incentives that I think many are not grasping.

The value of a commercial property is based on the rent that can be obtained. As rents go up, the building is worth more. As they go down, the building is worth less.

When obtaining commercial financing—when getting a loan—the value of the building will be appraised based on the rents that can be obtained. If you can collect a lot of rent, the bank will loan you a lot of money. If you can’t collect much rent, the bank is not going to loan you very much.

This is all pretty straightforward, right?

Let’s say a commercial property developer acquires a $1 million office building. First, they must put 20% down—$200,000. Likely half of that down payment comes from gap financing from a local bank(s) and the other half comes from investor cash. That means they will borrow $800,000 from a major bank—and that loan will be a financial instrument that will ultimately get sold onto a secondary market and securitized into different packages that are then sold in bundles around the world. It’s a very efficient capital allocation model.

To get that $800,000 loan, the developer is going to need to show collective rents that value the building at $1 million. For ease of calculation, let’s say they have seven different units in the building and collect $10,000 per year from each unit. That is $70,000 of revenue annually. That’s enough money to make their annual debt service of $52,000 on a 5% loan, and have some money left over for other things (maintenance, taxes, investor return, etc…).

Building Value: $1 million

Loan Amount (80%): $800,000

Annual Debt Service (5% interest): $52,000

Annual Rent Revenue (7 units x $10,000 per unit): $70,000

Now the developer owns the building and everything is going great until—oops—market glut. We’ve just built too many units in the market and, as things turn over, we’re not able to fill all the units at the $10,000 per year rate. In fact, ponder a situation where only four of the seven units are rented.

The developer has some options at this point. Option 1: Lower the rent to a level that fills the vacancies. Option 2: Convert the office space to some other use. Option 3: Stay put and hope that the vacancies are a momentary blip in the market and that new tenants will soon be secured at pre-vacancy rates.

Let’s take a close look at how the “marketplace”—which is how we’ve come to define our centralized, corporate/government financial system—works these things out.

Option 1: Lower the rent

With a sound grasp of free-market economics, the developer understands that supply and demand equilibrate with price. If the units don’t fill at $10,000 per year, then the price has to be lower.

Let’s overlook the impact this has on the four existing tenants who are paying the higher rate—sure, they have leases, but contracts are malleable and fluctuating prices tend to destabilize agreements—and just focus on filling the three vacant units. Let’s say our developer drops their prices by 20% and so the market clearing lease rate is now $8,000 per year.

Now the developer’s bringing in $64,000 per year instead of $70,000 per year. That’s okay. They’re still making their payment to the bank. They’re still keeping up with the maintenance. Their investors aren’t happy to take a haircut, but that’s part of the risk of investing. So, this is stable, right?

Not really. Commercial loans are generally financed over 3-, 5- and 7-year timeframes. That means every few years, the developer is going to have to roll over that loan. When they do, the value of the building is going to be based off the current market rent, which in our case, is now 20% less.

So instead of having a building that is worth $1 million, your building is now worth just $800,000. When you go to get your next loan, the bank is only going to lend you $640,000. And, in a falling market, they might be a little bit nervous about that.

Here’s the kicker: The developer has been making the loan payments every year and is completely current, but after five years, they still owe $735,000 on the initial $800,000 loan. Since they are only going to get a new loan at $640,000, they are going to have to come up with the difference—$95,000 in cash—before they can refinance.

Where is that money coming from? That’s a year and a half of rent! Is the investor going to kick that amount in? Not likely, since they are getting stiffed on their return already. Is another bank going to loan you that money? Possibly, but not likely, and certainly not at friendly terms.

The only real option is for the developer to take $95,000 out of their own pocket and put it into a declining building, something they are really not going to want to do. There is little to be gained at this point and nearly six figures to lose. You don’t last long in the development game doing things like that.

In summary, lowering rents to market price lowers the value of the building and makes the project insolvent. Game over.

Option 2: Convert from office space

Securities and Exchange Commission in Washington DC. Photo from SEC.

Remember that whole bundling and packaging thing with the original $800,000 loan? The people who made that happen—the banks, the agents, the brokers, the insurers, etc.,—they all deal with commercial office space. Their checklists and forms and paperwork are all dealing with a commercial office product. The stuff they report to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), let alone their investors around the world, stipulate that they are investing in commercial office paper.

The developer, who is not the owner of the building—it is the owners of those securities that technically own the building—is not able to unilaterally change the arrangement and make that commercial office paper into residential mortgage paper. If the developer does, there is going to be a lot of paperwork of the unhappy variety.

The developer could opt to refinance the building with a different financial arrangement, but they would be subjected to a very different set of rules and standards that would impact the value of that property. This would, almost certainly (unless residential rents were really high and practically guaranteed) bring about the same insolvency situation as simply lowering the rent, albeit with more paperwork.

And, since the developer specializes in commercial office space—and they probably do specialize, because it’s more efficient that way—making the shift to residential is not something they even feel qualified to do. The developer doesn’t have a lot of skin in the game at this point so why take on that turmoil? Game over.

Option 3: Ride it out

The developer keeps making their loan payment with three of seven units vacant. It’s not ideal, but it’s stable. Refinancing time comes and the developer can say – and the bank can verify – that the market rate in that building is $10,000 per year.

Yes, there are three vacancies and they’re making an effort to fill them, but they will be filled at the $10,000 rate like the four that are currently leased. Please, banker, continue to value the building at $1 million so we can roll this loan over and wait for the market to improve. In the business, this is called “extend and pretend.”

Here’s where the incentives for the bankers get interesting. If this is a local bank financing a local commercial product, the conversation probably gets rather personal. That local banker knows the local market and has a sense of what kinds of rents are possible. They are taking depositors’ money—literally the money of their neighbors—and investing it in this commercial enterprise. Hard questions are asked and whatever is finally agreed upon, we can guarantee the developer has some skin in the game.

Unfortunately, that’s not how banking works today. If the local bank has any involvement at all, it is as a broker—getting paid to make the transaction happen and then selling that commercial loan onto a secondary market—and so their main concern is twofold: (1) Getting paid the fees associated with the transaction and (2) making sure the loan meets the underwriting criteria and therefore can’t come back to bite them if and when it goes bad.

So, if the banker can legitimately certify that leases are in place to justify a $1 million valuation, that vacancies are only temporary and that there’s a good-faith effort underway to fill them at rates that justify the loan, then it’s all good.

This is why you’ll often see commercial space offered with free rent at the beginning of the contract. If the developer lowered the rent by 20%, then they become insolvent and are pushed into default. If they give you 20% of the rent for free—say the first year free on a five year lease—and the rest of the time charge you the elevated price, then they can claim the free months were just an incentive and the real market price is the elevated one they need the bank to certify. It’s the same dollar amount just expressed in two different ways.

If you understand these three options, you can start to understand why our federal policy has been to subsidize big banks and large investors through bailouts, artificially low-interest rates and money printing (aka quantitative easing). All of these policies elevate property values—commercial and residential—and give investors more time before there is a reckoning. Optimistically, in time, things may self-correct. This is the view of the central policymakers. Or failing that, those with money can build up enough of a buffer to withstand a severe downturn. Or, at the very least, the current policymakers will be the former policymakers and, well, in the long run, we’re all dead. So, don’t obsess over the future.

Understanding the Marketplace

Is this system a true marketplace? Yes, it is.

Is this system an efficient marketplace? Again, yes, it is.

So how can an efficient marketplace end up with persistently vacant properties and persistently high prices? That seems inefficient.

It is important to recognize what is really going on here, especially if we’re not happy with the outcome. What we have created is a marketplace designed to distribute capital as efficiently as possible under the theory that this will create the greatest amount of growth possible. I believe our system accomplishes those goals. If you are a macroeconomist, your indicators of success all measure positive.

While this system allocates capital efficiently, it does not allocate land or public resources efficiently. It optimizes one variable—the efficient distribution of capital—to the detriment of many others like unaffordable rents, unstable neighborhoods, vacancy rates, strained local government budgets and many more.

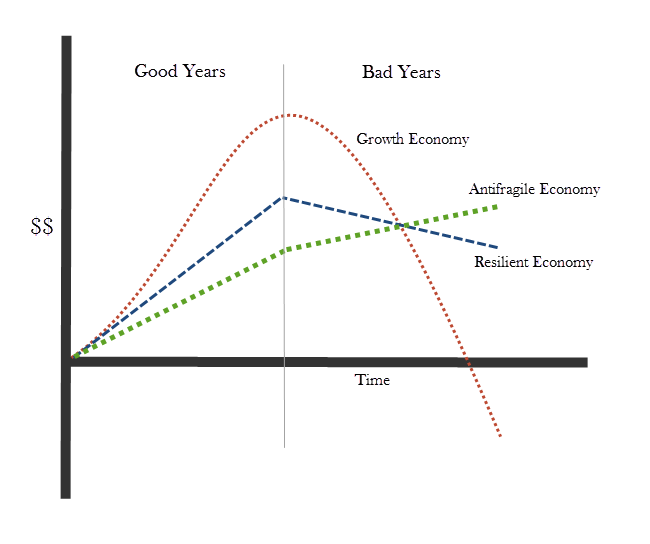

I wrote about this last year in my series on Tomas Sedlecak’s book The Economics of Good and Evil. In the Growth Economy that we have created, we maximize growth during the good years at the cost of our stability during the bad years. Right now, commercial real estate markets should be changing—and more generally, vacant retail and office space should be repurposed long before it fails—but that can’t happen because the marketplace we have set up for commercial real estate doesn’t consider this outcome. It’s a marketplace wired for growth. Period.

In the Resilient Economy (or, better yet, the Antifragile Economy,) we create a marketplace that balances competing objectives. Growth is one objective, but so is long term stability. We can have growth, but we can also have buildings that are free to adapt to changing market conditions.

I would argue, in fact, that such a marketplace—which would be far less centralized and corporate and far more localized—is actually closer to an ostensibly “free” market, where participants are freer to optimize the things they find most important, not just the centralized distribution of capital.

Don’t get fooled into believing that the crazy distortions we see in housing and real estate can only be solved by centralized interventions, be they corporate or government actions (or, even worse, combined corporate/government action). Our centralized marketplace optimizes very few variables. Only at the local level do we have the nuance available to us to overcome this limited set of options and start creating something that works for everyone.

(Top image from MoneyBlogNewz.)

Most local housing markets in the U.S. are oligopolies: new construction is dominated overwhelmingly by only a few developers. How did we get here, and why is it this bad news for housing affordability, as well as for our cities’ financial strength and resilience?